- Home

- Francis Carco

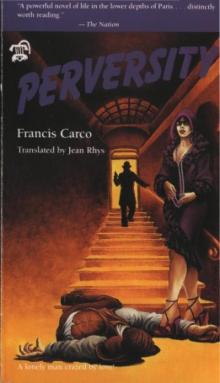

Perversity

Perversity Read online

Perversity

Francis Carco

* * *

Perversity

Francis Carco

This page formatted 2005 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

PART ONE. The Thin Partition

PART TWO. Student in Sin

PART THREE. The Room Downstairs

PART FOUR. Portrait of the Love Merchant

* * *

PART ONE.The Thin Partition

I

Irma's room was at the end of a narrow passage, on the right, and to get to it one passed a door which was always shut. The girl would say to each new client: “Don't make a noise,voyons!”

“Why?”

“He's asleep.”

“Who is?”

“My brother.” She explained that her brother worked as a clerk in an office and went off very early in the morning.

Then she would add quickly: “But don't be afraid, darling. In my room we'll be quite quiet, and you know, I'll undress.”

Irma the red haired was not lying. Emile had lived with her for five years, on the fourth floor of that house where at nightfall prostitutes of all ages went up and down accompanied by strange men. The women lived in an utterly careless disorder. The miserable staircase was lit by oil lamps and smelt abominably of drains, the damp walls were covered with scratches, the doors were badly fitting, the floors uneven. Thus they had always lived and their sordid surroundings were a part of themselves. Irma was accustomed to it all.

She was a rather pretty girl, small, plump, carelessly gay, still young, nicknamed La Rouque, the Red One, because of the red gold hair which she wore cut short at the nape of her neck. She was used to this brother older than herself, he was a part of her life. He slept most of the time, she tried not to disturb him, and thought no more of him.

She was generally to be found on the Boulevard de Crenelle, under the high, funeral-like gallery of the Metro, or at Jules in the Rue de l'Avre, a bar frequented by colored men, who on a Saturday would wait there for her. In order to be sure of a certain sum, she had made the whole band a fixed price for that evening, and though it was sometimes difficult, she kept her engagement strictly and never disappointed one of them.

All next day she would sleep, a heavy sleep which looked like death—a murder.

In the next room Emile also slept. On Sundays, he stayed in bed till six or seven o'clock. Then he got up, went out, ate in a restaurant and spent the evening at a cinema.

Tall, round shouldered, taciturn, always tidily dressed in clothes too large for him and shiny with wear, he had neither acquaintances nor friends. He lived a solitary life organized to fit in with his hours of work. Every morning at seven o'clock he descended his four flights of stairs, every evening at dinnertime he mounted them again, and the Ladies whom he met on the staircase, without seeming to notice them, never once happened to find him late.

The street was black, almost deserted. Here and there badly lit shops threw oblique, reddish gleams on to the pavements.

“Yes,” resumed one of the women. “I don't care for that man.”

“Neither do I.”

“Types like that,” declared a third, “don't talk much, they do things on the quiet.Ou-la-la! I've known some others of the sort. One does not even know that they are there. Then one day pan! and their portrait in all the newspapers.”

“You are right.”

“Unless they take to drink,” concluded an innocent and very ancient creature who was derisively known as Belle-Amour—Pretty Love.

“Drink saves them from themselves. They are nice when they are drunk.” And Belle-Amour's face lit up at the enlivening idea of drink.

She had a real adoration for Emile. A man so exact in his habits astounded her. Also she admired him because instead of living upon La Rouque, and notwithstanding his air of sullen suffering, he went every day to his office, he came back every night without fail at a fixed hour.

In the evening she watched from the street for his return, and when his mean figure appeared she was quite moved. Nevertheless she did not dare to speak to Emile, who with his uncertain gait would enter the passage and climb the stairs. She listened to him going up, crossed the street and watched the fourth story window light up. Then she would begin her walk up and down past the black houses, a shadow from which people drew back.

***

Up in his room Emile hung his cap on a nail in the passage.

“Is that you?” called Irma.

“Yes, yes, it's me.”

After he had taken off his coat, he said to her in his small falsetto voice: “Good evening.”

She answered, “Good evening.”

Emile never went into his sister's room. From his own room he would pass into the narrow kitchen where he took off his shoes; they were heavy, iron nailed, and fell noisily on to the stone floor. And that was all. The man put on his slippers, then silently pulled a knife out of his pocket, took bread and wine from a cupboard, and a plate upon which was a piece of cold meat or of cheese, sat down.... He ate like this every evening, leaning on the table as if on a desk, cutting the bread and meat on his thumb absent-mindedly, and chewing his food with effort.

From her room, Irma could see him under the crude gaslight and sometimes he watched her while she dressed, with sad and vacant eyes. He stared at her as an animal stares at things and people. What could he be thinking of? Not that Irma bothered about him, and when she had gone out and shut the door behind her, Emile went on eating silently and poured himself out a glass of wine.

He felt more at ease when he was alone, calculated with seriousness the best way to make himself comfortable, yawned, meditated. The man had an abnormal need of sleep and this gave him, even when he was awake, a morose and dreamy expression.

Sometimes it took him longer than a blind man to stand up or move, and when he hurried he seemed to be groping uncertainly in the dark. He had to plan everything he did carefully, and his effort was quite out of proportion to the very small result obtained.

This singularity was obvious from the first, but one got used to his painful and complicated method of seeking himself in the shadows as it were, and one ceased to notice it.

***

There was something alarming about Emile at first sight, his big body, his long legs, his expression of stupefaction, his drooping moustaches of an ugly yellow. He terrified the children of the Quarter, they instinctively avoided him. Though he was so harmless, all the little servant girls going on their errands stopped disconcerted if they met him, and prudently drew aside to let him pass. He went on his way without even looking at them.

Even Irma, when she heard him coming, would often shiver a little with fear.

However she knew Emile, and she was used to his strangeness. She had always noticed that look of an automaton which secretly repelled everybody with whom he came in contact. His first wife, now dead, had all her life tried vainly to conquer the morbid numbness that estranged him from everything. He had not changed. At the age of thirty-five, in June, 1914, Emile married again—a widow who first betrayed him and finally left him after the war to go and live with a Belgian in his country. Emile did not seem at all affected by this event, and merely went to live in a hotel. Sometime afterwards he suggested to his sister, apparently for motives of economy which she shared, that they should live together, and he settled in her lodgings.

II

He thought that he was in a place where, notwithstanding Irma's comings and goings, his comfort would be the first consideration. Then one night, towards midnight, he was awakened by an unusual noise. Emile listened. In La Rouque's room a man was talking without troubling to lower his voice, and the girl—far from silencing the speaker—answered with animation. Once or twice

Emile heard a laugh, and protested by a grunt.

“He chut! chut!” then said Irma, but too late. Emile was awake. He sat up in bed and asked weakly: “Is this noise going on for long?”

Someone answered at once: “No, no, all right.”

“Annoying people!” grumbled Emile. “Keeping people from sleeping!”

He waited, leaning on his elbow, then plunged into the bedclothes and shut his eyes. But he could not sleep. He tossed and turned, and perhaps for the first time began to picture his sister with a stranger—laughing and talking. He had never till the present moment dwelt on the thought of Irma in her room accomplishing her nightly task. But because he had been disturbed in his sleep, Emile confusedly began to imagine the scene which was taking place on the other side of the partition. He was not shocked. He was irritated, filled with ill temper and discontent. Certainly what Irma did was not his business, but why was she making such a noise? It was intolerable. At this time of night Emile did not admit this loud talking. Were they laughing at him? Did they mean to be personally disagreeable to him?

He grumbled: “If it begins again I'll—”

The idea that they were doing it on purpose was provoking, and he was on the point of telling his sister that she must keep quiet, when a moaning sound, at first almost inaudible, but which grew louder, came from the next room, and Emile knew no more what to think. It was Irma moaning, and to her complaint the creaking of the bed added a cynical and degrading confession.

Then all that had gone before became precise to Emile's eyes, assailed him with such force that he dared ask himself nothing more. “Ah well,” he thought, “well... well... Surely.” His wrath cooled down, and gave place to a feeling of stupor which increased as Irma's sighs became more numerous and hoarser. The sounds reached him through the partition, as in a hospital the panting breath of a sick man dreaming can be heard by the helpless person in the next bed. Emile found himself in an exactly similar situation. He was unable to do anything, and could only wait for La Rouque to stop crying out from the next room her detestable and painful pleasure. Then she sometimes found pleasure? Emile felt humiliated at the idea. And with whom? He was curious about the unknown man. What could he be like? It was extraordinary. Emile could not picture him. The more he thought about it the more complex became his imaginings, his brain accumulating a hundred preposterous, grotesque and unlikely details.

Sometimes he told himself that there could be nothing very special about the individual. Sometimes on the contrary, Emile imagined him with striking features and an air which would force every one to notice him. And this idea was a very painful one. It was tormenting, for in order to react he was unconsciously comparing himself and opposing himself to the unknown. Alas! Emile had never given pleasure to a woman. He had done his best. But no! Never! Never to a single one. He had married two indolent and vulgar creatures: one had frankly disliked “the business,” the other had betrayed him the day after his marriage, and in his own house. Women were a detestable lot. Evidently he could have consoled himself with somebody else, but this he did not dream of doing. He thought far too highly of his own modest person to risk another adventure. The girls of the street did not tempt him. As for the women who awaited his choice in the different brothels of the quarter, the thought of them disgusted instead of pleasing him.

He sincerely felt that the best way of dealing with women was to carefully avoid them, to keep them at a proper distance. Once seduced by one of the creatures, what did a male become? A nincompoop. An imbecile. He knew it. He had paid dearly to know it—too dearly for what it was worth.Ou-la-la! Too dearly. Much too dearly... And from that experience had come his need to live alone, to avoid people, to occupy himself with his own comfort, to shut himself up every night at nine o'clock in his room and sleep. People could think what they like about him. So much the better. At any rate he was left in peace; and that was all he wanted. All his unhappiness had been caused by those two beings and they were associated in his mind—the dead woman and the unfaithful one. He condemned them both with severity.

And now, just when he hoped to arrange some possible sort of existence, Irma had interfered, and reopened the whole question. Emile felt that he was losing his temper, and if he made an effort to be patient, it was because of an obscure sentiment which he had for this sister, and of which, secretly, he was ashamed. Did La Rouque know that from his room he could hear everything that went on? She certainly did. And this sad certainty increased Emile's irritation, obliged him to realize that Irma, when she felt so inclined, did not bother about a soul except herself. The whole night passed in this way. The man said something, got up, lay down again. Irma answered him and in her turn go up. The noise of water being poured out of the basin, of bare feet on the floor, succeeded to all the other noises. Then everything began all over again, and Emile meanwhile heard the ticking of his watch hung on the wall and wondered what the time was. He grumbled, agitated. What a night! It seemed to him that it would never end. The blood throbbed in his temples. The nerves knotted themselves in his legs and hands. He stiffened himself in vain, it was impossible to keep still; and when the dawn, a thousand times delayed—so he thought—paled between the shutters, it found him with wide open eyes amongst his disordered sheets, and his coverlet rolled into a ball. Emile got up quickly. He felt broken with fatigue, like those torpid animals whom one can see every morning moving between the shafts of the carts in the Halles is if they were walking in their sleep. He dressed himself, vent into the kitchen, took this shoes. The sink smelt abominably badly. He went back into his room. He acted mechanically, without thinking of what he was doing, an idea, strong, deeply rooted, had taken possession of him: he wished to see and never forget the man who was now sleeping at Irma's side. This idea was absorbing and paralyzing. He stared at the shoes in his hand for a long time, thinking of the unknown, and telling himself over and over again that now at last he would know what he was like. However he could not quite make up his mind. Something which he could not quite define stopped him, held him back....

Suddenly the clattering of the milkman's cart, which woke him every morning, sounded from the street. Emile recovered himself. He realized that everything inside him and around him was getting to work again. He placed his shoes under a chair with care, went softly into the passage, opening Irma's door, approached the bed slowly and looked. The man and the girl were lying asleep. He was stretched out on his back quite naked, his mouth open, one arm thrust under the pillow; she was buried like a dead person under a big eiderdown.

Emile looked closer. The sleeper's chest was covered with blue tattoo marks. A hand of Fatma and a dagger ornamented the left arm. Emile noticed also near the wrist three stars, cut deeply, and a name—Gilberte. Underneath were the letters P.L.V.

He asked himself what these mysterious letters could mean. He had not the least idea. And after all what did it matter? Emile had eyes only for the man stretched out inert on the bed. His hair was frizzy and he seemed to be small but robust. Emile was going to leave the room when he noticed particularly a long scar on the right side—of rose so pale that it astonished him.

III

Emile did not speak to his sister when he came in that evening. He shut himself up at once in the kitchen and took off his shoes. La Rouque let him alone. She did not wish to argue and was completely indifferent to Emile's bad temper. So much the worse for him. What an idea to behave like a child. At his age!

“Go on. Go on,” she said to herself, “sulk if you want to. Make a fool of yourself. We'll see what will be the end of it; you bet I don't care.”

She was repeating in a low voice: “Make a fool of yourself. Yes, yes, that's it—make a fool of yourself,” when the door opened and Emile asked: “What are you mumbling about?”

“Oh, shut up and leave me alone!”

“Come here,” said Emile.

La Rouque was standing before a piece of broken looking-glass nailed to the wall, gazing at herself.

“D

o you hear me?” repeated Emile angrily.

“Well, what is it?” she said without moving. “You've got the jumps this evening.”

“Filth!”

“Filth?”

The girl turned.

“Why do you insult me?” she asked. “What right have you to insult me?”

“Right or no right,” he answered, “I don't care. Understand me well. I won't have it. I won't stand it. You're not going to start last night over again, I tell you. Not in this house.”

“Who—me?”

“Yes.”

“But last night,” answered La Rouque, “was not my fault. I had someone with me. No—but joking apart, you'll allow me, when I have a man to sleep with, not to spit on him.”

“Oh, that's enough, that's enough!” shouted Emile.

“What do you take me for? Those sorts of men are better left outside.”

La Rouque began to laugh.

“Stop laughing,” said Emile walking up to her. He was becoming more and more angry. “You're mad... quite. Do you think...”

“He la, I warn you,” said Irma coolly, “that if you touch me, I'll give it to you back.”

“What?”

“I will,” she declared. “Monsieur is not pleased, and he must make a noise about it. No, no, my old boy. Nothing doing.”

Emile stopped stupefied. She went on: “This place belongs to me to begin with, and I'll do what I like in it.”

“That means?”

“It means,” explained Irma quietly, “that if I want to bring anybody here for the night, I'll bring him.”

“Irma!”

“Irma—nothing. You heard what I said.”

She went back to her looking-glass, took a comb and began to comb her hair, keeping an eye on Emile who stupidly shook his head and panted with rage. She threw her hair back and smoothed it on to her forehead.

“Oh, you're pretty,” he mocked, “you're a sweet thing.”

“Possible.”

“Certain,” said Emile. “It's true that anything is good enough for the dirty dog who was here last night.”

Perversity

Perversity